-

Work@AXA

Work@AXAAXA Hackathon: Focus on innovation

-

Mobility

MobilityWildlife vehicle collision: what to do and where to be careful

-

Work@AXA

Work@AXAWorking as a GenAI Engineer at AXA

-

Trend

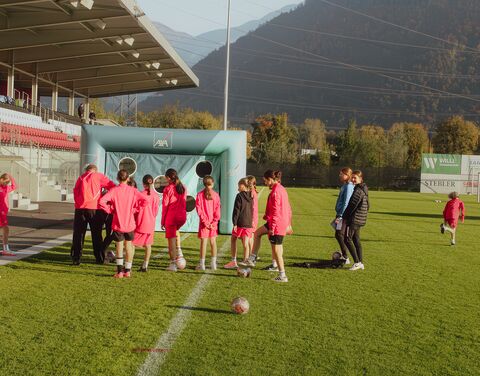

TrendVolunteering at UEFA Women’s EURO 2025

-

Trend

TrendWild haymaking on the roof of Europe

-

Trend

TrendClearing shrubs in the southern valleys of Graubünden

-

Mobility

MobilityCell phone thefts: Damages amounting to millions

-

Work@AXA

Work@AXASports and education: Here’s how the balancing act works

-

Trend

TrendWEURO 2025 in St. Gallen: A host city gets ready

-

Mobility

MobilityCar ranking: Where the most expensive, newest, and heaviest cars are driven

-

Mobility

MobilityBike thefts cause millions in claims

-

Trend

TrendStrong together: AXA and Caritas support single parents